Young People’s Transitions from Precarious Work in China and South Africa webinar

Globally, young people are increasingly entering the labour market via precarious work forms such as internships and zero-hour contracts. While precarious work has been increasing for some time, the growing “gig economy” has contributed to the expansion of such work. In South Africa, policymakers and practitioners sometimes consider such occupations as a cure to the country’s vast and growing youth unemployment problem. Many people believe that any employment experience, no matter how precarious, will lead secure jobs in the future. However, there is little evidence to suggest that this is the case, either globally or in South Africa specifically.

The Precarious Work and Future Careers (PWFC) project, funded by the British Academy and conducted by the Centre for Social Development in Africa at the University of Johannesburg in collaboration with the University of Glasgow and Tianjin University, sought to determine whether early precarious work experiences lead to longer-term careers, what types of work experiences offer greater benefits in terms of longer-term career stability and if there are any potential links between differing outcomes and each country’s economic, labour market, and social welfare policy environments.

Dr Lesley Doyle (University of Glasgow) began the webinar by framing the PWFC project. The webinars’ purpose was to analyse the labour market trajectories of a sample of youth over time, using equivalent panel datasets and to assess whether assumptions that engagement in precarious work leads to later secure careers hold true. The webinar was based on work from the PWFC project. Lesley highlighted that the main aim of the project is to inform policy in the context of the post-Covid-19 recovery period and the growth of the gig economy.

Dr Geng Wang (Tianjin University) and Mr Zhonghan Wang (Zhejiang University) presented the China case study. Dr Wang explained that precarious work in the Chinese context could be attributed to global capitalism, while others felt that there is a long history of precarious work forms in China. Mr Zhonghan Wang showed that the majority (60.38%) of precarious workers are male, and about 70% reside in rural areas and about half of them have only completed middle school. Over 80% of precarious workers were working in the private sector. The income of these precarious workers did show an upward trend over time, however the difference in income between precarious workers and those in stable employment was also increasing indicating growing inequality in wages.

The China case study also showed that only 27% of precarious workers managed to move into stable employment over time.

Dr Wang ended off with the policy implications:

- There is very little social protection for precarious workers which has created a deeply segmented workforce.

- Employers of precarious workers don’t provide other incentives such as medical cover, housing etc.

- Employers also don’t invest in these workers and don’t value upskilling them as they are seen as short-term.

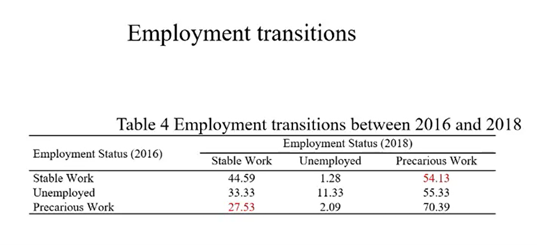

Viwe Dikoko, CSDA researcher, spoke about the findings from the South African case study. The findings showed that 88% of the sample are African and that 69% of the sample were engaged in precarious employment (in the first wave of data). The study showed that only 14% of people who were in precarious employment ever moved into stable work. 53% of the participants remained in precarious work and 31% moved into unemployment in the next wave. This shows that it is incredibly difficult for precarious workers to move into stable work over time.

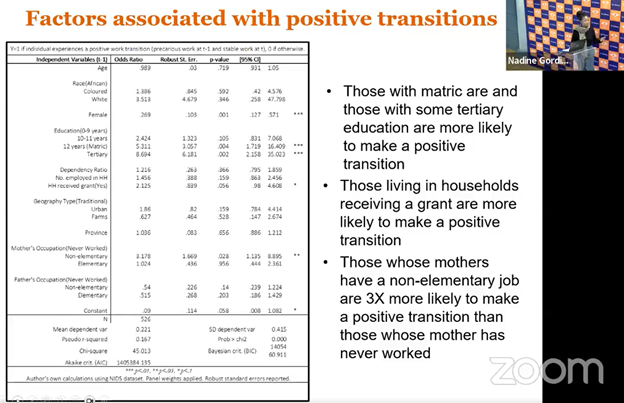

The study looked at the factors associated with positive transitions.

Prof Lauren Graham discussed the implications of these findings:

- Once a person is in precarious employment, it is very difficult for them to transition out of it.

- Precarious workers are particularly vulnerable to unemployment.

- Education is key to providing pathways out of precarious work.

- Grants also play a role, and these gains should be leveraged for improved outcomes.

- We also need to think about the role and the responsibility of the private sector in creating decent work.

The webinar also featured Dr Yisu Zhou an Associate professor of education policy at the University of Macau as a discussant. He commented that the cross-national comparison aspect of the study makes the cases very interesting.